M&A and its tax risks

Some of you might have noticed the news about Softbank Group K.K., a large Japanese communication company, released on April 18th media.

The news attracted many people for its significance in terms of tax leakage amount.

However, I was attracted to a comment made by the firm’s corporate communication below.

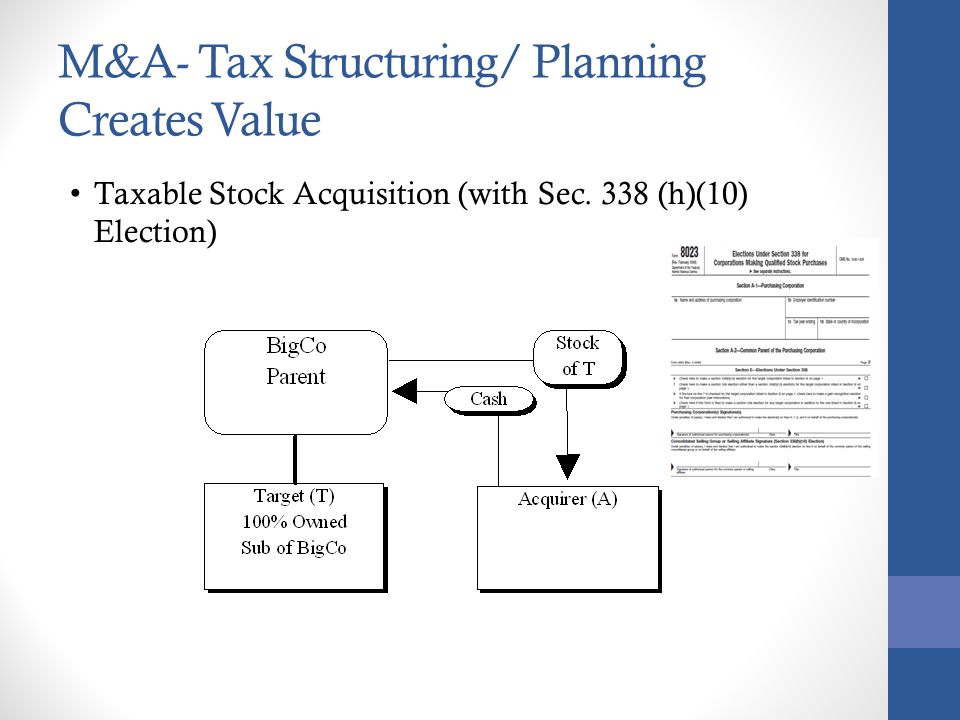

(Incidentally, the above picture describes typical M&A scheme prevailing in U.S. but nothing to do with the Softbank case.)

” The firm should have identified and discussed tax implication of all of Controlled Foreign Corporation underneath Sprint and Brightstar immediately after the the firm acquired them. The firm have taken majors to prevent recurrence of this issue.” (April 18, 2018 the Nikkei internet news)

Table of Contents

Anti Tax Heaven Legislation

Anti Tax Heaven Legislation is a Japanese tax rule requires a Japanese parent company report its taxable income pooled outside Japan through its Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) in low or no tax jurisdiction such as the Cayman Islands (so called Tax Heaven) in the case where such tax deferral has no business and economic rationale.

It seems that Softbank had realized necessity of the tax reporting after tax auditors came and filed amended tax returns.

The firm should have reported taxable income pooled in its CFCs and paid corporate income tax on such CFCs’s income to the Japanese government under the Anti Tax Heaven Legislation.

I used to prepare massive numbers of tax return forms for CFC (by hand writing) when I was working for a Japanese leasing company about 25-year ago.

The company leased many (could be hundreds) cargo ships to foreign operators through CFCs established one by one as a lessor of each ship.

As most of such CFCs were in tax heaven, the firm had to file thick tax return schedules to report CFC status and taxable income.

Although my main task was not tax but consolidated financial reporting preparation of CFC tax return schedule was assigned to me just because CFCs were consolidated subsidiaries for financial reporting and I was the most junior person in that team.

As a matter of fact, there was no income pooled in the CFCs (it might be the reason the tax return team was less motivated to take care of CFC) however the firm had to prove it by filing CFC schedule. So someone had to take care of it.

Knowing ”Stepchildren” is tough job

In addition to burden of proof, economic substance test of tax deferral is troublesome.

There seemed be a disagreement between Softbank and Japanese tax authorities on the economic substance test.

When I worked in a foreign financial firm, I helped bankers in M&.A division estimate CFC taxable income underneath target company as a part of due-diligence process. It was really tough job because the company owned so many subsidiaries of which business activity was not well known.

If they were established by the target company, it could have been easier to confirm their business profile. But the company had only little information on them as most of them were established by others and became its subsidiaries after series of M&A.

Under such situation, it is quite difficult to know profile of CFC necessary for tax filing then likely end up with the same outcome to Softbank.

Need to accept “everything” of CFC

Timely due-diligence process is key for successful M&A. So bankers tend to pay less attention to tax implication due to time constraint.

Putting provisions for “defect warranty liability” or “representation and warranty” in M&A agreement may be practical solution to mitigate the risk. But it would be difficult to convince a seller take all tax risks as tax implication on CFC is complex and unforeseeable.

I have no idea whether Softbank’s tax risks associated with Sprint/Brightstar had been hedged but cannnot help sympathize with the firm.

as I can sense how the firm struggled with CFC from comment of its Corporate Commucation above.